The Price of Being Right

I like being right. A lot. However, being right sometimes comes with a high price tag, as I found out yesterday.

Here’s the scene: In preparation for Giacomo’s surgery, I was told to anticipate a 2-week ICU stay to stabilize his breathing, amongst other things. At home, he currently gets great breathing support with his BiPAP machine, since his body isn’t strong enough to inhale enough oxygen and exhale enough carbon dioxide as soon as he falls asleep, in addition to that whole obstructive sleep apnea thing. His current mask covers both his mouth and nose, putting some pressure on his jaw, so with the major surgery in that area, extra pressure is not really a thing we want during the healing process. To deal with all this, and keep my guy breathing, it had been my thought that he would very likely get a tracheostomy tube placed.

About two weeks ago, all that changed, starting the cascade of events the led to what we are now calling “an unfortunate experiment.”

In finalizing surgical plans, it was brought to my attention that they were not planning to put in a tracheostomy tube, but had a plan to use the nasal mask for his BiPAP, which would not put pressure on the jaw. I was instantly skeptical, since A. When he first got his BiPAP and tried to use a nasal mask, it was an epic failure as he was not at all interested in breathing through his nose since B. He is NOT a nose-breathing kind of guy and never has been. I have brought up this skepticism in his ability to suddenly decide to breath through his nose to every single provider, nurse, and basically, every person who has come in contact with him, save for the one changing his garbages. I have told them, “Even if you are not responsible for his breathing, I want you to know that I am really concerned about this plan, and I just want to be sure that I have voiced my concern to as many people as possible, just in case.”

During his surgery, Giacomo was intubated on a breathing tube through his nose, which was ideal, to keep his mouth closed and allow for good healing in his jaw that was broken, repositioned and now pinned/screwed in a new place, with tight rubber bands and a splint adding additional support. Post-op he headed to the ICU with the tube still in place, something I had been told would be there for a little while as we ensured that he was stable. Keep in mind, when someone has myotonic dystrophy, general anesthesia itself and some of the medications used can be fatal, but often it’s the post-anesthesia problems that pose an issue, as it can take a long time for them to be able to handle secretions and to be able to breathe on their own without the ventilator support, making aspiration pneumonia and respiratory failure some pretty major issues. Knowing all this, along with my already-raised concerns, you can imagine my discontent when an ICU doctor, who I had never met before, stopped me before I even entered Giacomo’s room to inform me that they were planning to pull his tube nearly immediately.

Enter the roar of the tiger mama.

I firmly explained to this doctor that this was not the plan, as we needed to not rush things and keep him safe in order to minimize complications. I inquired if he was familiar with his disease and issues post-anesthesia, and he said, condescendingly, “Oh, yeah, his obstructive pulmonary disease?’

I, in my best calm roar possible, replied, “Actually I’m referring to his myotonic muscular dystrophy, which is primary to the obstructive pulmonary disease. You’ve read his chart right, and seen that is his primary diagnosis? And you also know about all of the post-op complications related to anesthesia, right?”

The condescending doctor replies, “Oh, yeah. Sure.”

I, tiger mama, am unconvinced with his cavalier reply. “So, you know that he is at a huge risk of respiratory failure and aspiration pneumonia now, right? So we’re going to leave that tube in. And you’re going to page his pulmonologist, right?”

I think you all can imagine that, at that moment, the tube stayed in and they paged pulmonology.

A few hours later Giacomo’s pulmonologist from his clinic, as well as the one from the ICU, showed up. I, again, expressed my concerns about extubating him. I was unpleasantly shocked that the doc who has been following him and his siblings, specifically related to their disease thought it was a good idea. I realized, at that moment, her part in the change of plans, as she claimed it would be totally fine and they would just put him straight on the BiPAP with that nasal mask and he would have no choice but to breathe through it since his mouth was now surgically closed. I, on the other hand, reminded her of the nearly 15 years of mouth breathing he is accustomed to, and told her I was worried, as I shed my first tears of this whole ordeal, reminding her that they needed to be sure he could breathe and that he had endured too much with his mouth leading up to this for them to put his life at risk and not be able to reap the benefits of this surgery.

“And what if you’re wrong and I am right? What if he doesn’t make that choice to breathe through his nose?” I asked her.

“Well, then we just reintubate him.”

I found this easier said than done, knowing it had taken about an hour and a half to finish prepping him for surgery once he was in the OR, a significant amount of that time spent intubating him. She goes on and on about how she really thinks this will be fine now that they have changed his anatomy. I go on to explain how anatomy is one thing, and functionality is another. This is something I have said at least 10,000 times to new families who have babies struggling to feed well when they have oral restrictions or challenges, challenges that can be overcome with time, exercises, practice, etc, but will not change immediately since the baby has been sucking improperly for a number of months at that point from practice in utero, plus their time spent outside the womb. I am talking to her about 15 YEARS of refusal to breathe through his nose.

Mid-argument, with tears of frustration, still flowing, my new best friend, the charge nurse who just happened to be in our room, spoke up.

“Her concerns are valid!”

Then her colleague, the ICU pulmonologist who also is now on his way to becoming my new best friend spoke up as well.

“I don’t think it’s a good idea to extubate him at all right now.”

Yes! I love these people! Finally, someone is listening!! He goes on to make a plan to override the other doctor’s opinion, keep the tube in overnight, and not try take it out until a lot of hands are on deck, including a critical airway team, who can get that tube back in quickly in the event that I, his mother, caregiver, advocate, and the person who knows him better than anyone in the world, happen to be right.

Overnight things are great, and G is happily sedated and intubated with no real events to note. I actually slept a few hours and started yesterday full of that hope that I have been harvesting all these years. Morning rounds go well, and I think we have a plan to gently remove him from the sedation, slowly decrease the assistance the ventilator is giving him to see if he might be inspired to breathe on his own again, and then give the tube removal a try, with that attempt to put the nasal mask and the BiPAP a whirl. I AGAIN voice my concerns to everyone who comes in contact with me and my guy. Some are listening. Unfortunately, the ones listening don’t have the pull to make the potential life-altering decisions of whether or not to pull out my son’s breathing tube.

Around 1:30 things start to happen, quickly. While G’s regular nurse is on break, someone comes in and tells the one filling in to turn off the propofol sedative and get ready because it will wear off quickly and he will start to come to rapidly. They take out his arterial line that has been giving consistent and accurate blood pressures plus a place to draw blood from. They pull his foley catheter before he’s fully awake. We have to hold his hands back away from the tube as both he starts waving them and moving his feet in sync as though he’s trying to climb through a tunnel. One of the residents comes in ready to pull the tube. I peek out the curtain and see a group of people outside I presume and soon realize are the critical airway team.

The doctor asks Giacomo to open his eyes. He shakes his head, “No.” He asks again. Same response. I ask him. He shakes his head again, “No.” The doctor presumes that he’s alert enough since he’s responding, even though he refuses to open his eyes. I tell him that I’m there that he’s got a tube in his nose helping him breathe and they want to take it out. I ask if he wants his music, the “Surgery Survival Songs” playlist that he and I made together. He shakes his head, “No.” The doctor asks G if he wants him to take the breathing tube out of his nose. He shakes his head, “No.” The doctor comments, “Wow, I’ve never had anybody say that they don’t want the tube out before!” Giacomo keeps shaking his head. I see him raise his right fist in the air, something he does when he’s angry and is often followed by the statement, “You’re violating my rights!!” I see my fears about to be realized at that moment, as my boy is so adamant about not only his wants but his needs.

Then the doctor pulls the tube. They put the nasal mask and BiPAP on. He listens for breath sounds. There are none. Just as I knew there would be the case. He asks me, “Is his breathing normally shallow?” I look at him and tell him, “No. I told you all he can’t breathe through his nose. He’s not breathing.” The Jaw Bra holding his mouth shut slips off as the chaos starts and he gets his mouth open about half a centimeter and finds a hint of breath between his swollen mouth and immobile jaw. The doctor says, “Oh, he’s breathing a little now!” I point out to him that it’s because his mouth is open. His chest barely moves. I look up at his oxygen saturation as it plummets from the 80’s, 70’s, 20’s.

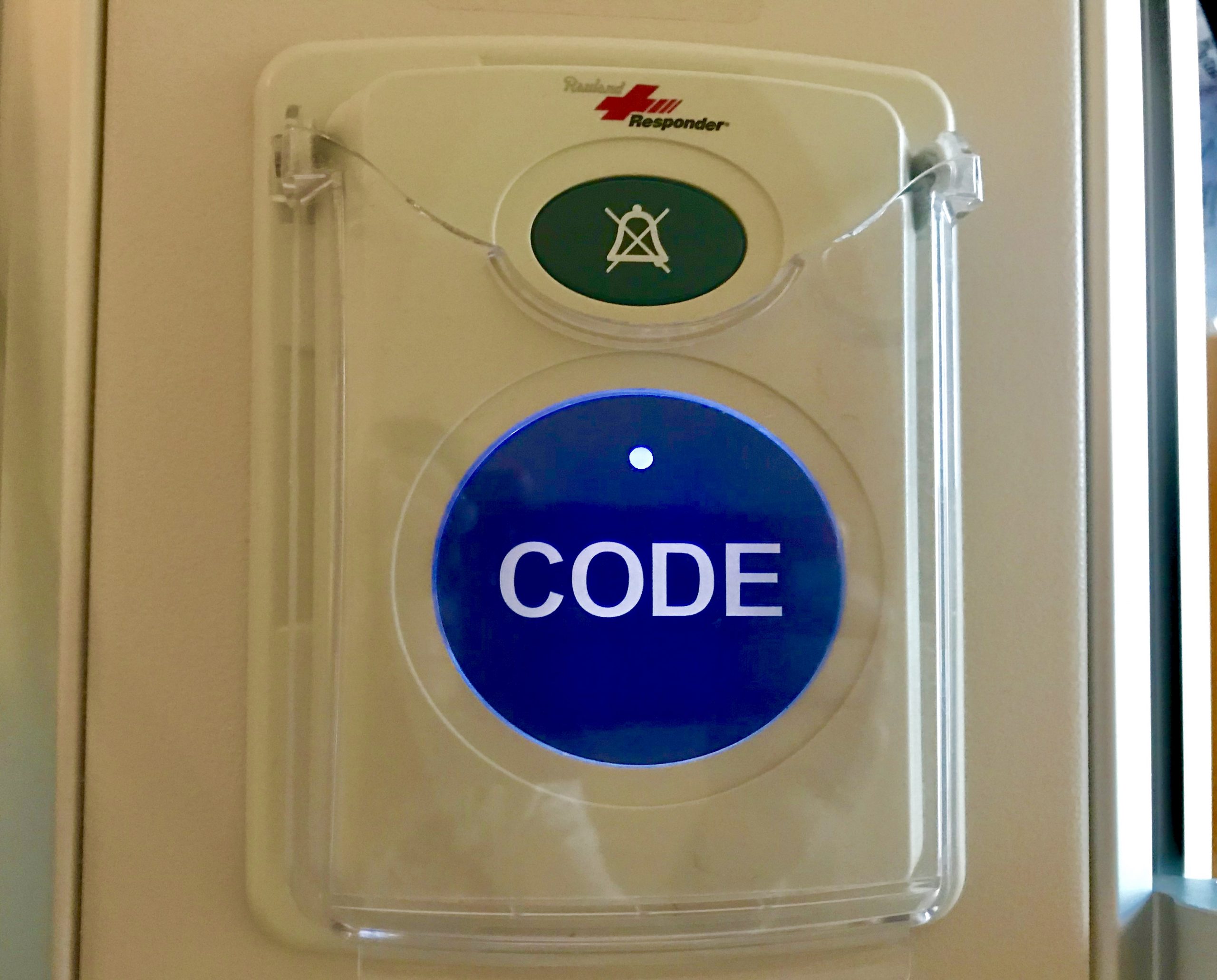

Code Blue.

The button is pushed. The call is made. So many people rush in I can’t even begin to count. They begin to bag him.

“Stay with me, Giacomo!! Stay with me!” I calmly but firmly tell my boy, as the tears stream down my face. He’s not moving. I see him start to give up. I feel him leaving me. “At what point are you going to reintubate him????!!!” I shout to them. They tell me they are going to now.

They keep bagging him. There is blood coming out of his mouth and his nose as I watch them simultaneously try to save his life and potentially destroy the surgery he has been waiting for and endured so much to prepare for, the one that was supposed to improve his quality of life not take it away. “You need to suction him!” I call out to the team. “You can’t let him aspirate!” They pause from the bagging and suction a little, then back to keeping air in his lungs, lungs that, until moments before were full of air, until they took it all away as a horrible experiment and what will likely be a future training example of what happens when you don’t listen to a patient and their caregiver.

I see the anesthesiologist from Monday’s surgery enter the room, the guy who was able to get a breathing tube down G’s tiny nasal passage, that day, with a great deal of time and patience. We don’t have that kind of time. He briefly tries to get a new tube in his other nostril, but even with his incredible skills and fiber optic camera, everything is too swollen. He grabs the emergency scissors that have been taped at the head of Giacomo’s bed in the event that we needed to cut the rubber bands holding his upper and lower jaws together, as an extra layer of protection to the 10 titanium screws placed during surgery. He looks at me and tells me this is critical and he as no choice but to go through his mouth.

“Don’t leave me, buddy!! Stay with me! It’s not time!!” I repeat these words over and over. I call out to whatever higher power might be listening as I watch my boy keep slipping away. I beg him to come back.

And then the tube is in. His oxygen saturation is back. The chaos begins to calm. The crowd slowly begins to retreat. I step out into the hallway to catch my breath, along with a couple of doctors, both one who pulled the tube and another who assured me it would be “fine” earlier that morning.

“I guess you were right,” one of them says to me. I did not yell or shout. I wiped the rest of the tears from my eyes and this tiger mama, very clearly spoke, in a way that they finally heard.

“I told ALL of you that this would happen as soon as you pulled the tube. I told ALL of you that he is NOT an obligatory nose breather. And you didn’t listen. HE told you not to take it out. And now look at what happened. You have all learned a very valuable lesson here today.”

I have never hated being right more in my entire life.

And what happens now? He is alive. He is sedated. He is back on the ventilator, for an undetermined amount of time, but likely at least a few days, but possibly longer, recovering from excessive amounts of swelling, bleeding, a partially collapsed lung, and the unnecessary trauma of this unfortunate experiment in Giacomo’s respiratory capabilities. People are listening to me, as I have made it pretty damn clear that no one will come near his airway without a plan that helps him in the immediate, short term, and long term, and also maintains the integrity of his surgery and the awesome new jaw they have created for him, so that he can actually live and enjoy it. I am calling upon every possible provider to get on this team. I have told them that they need to take this unique person, with a rare disease, with unique manifestations and symptoms, who just had a surgery that is rarely done on people like him, and they need to come up with a strategy that will work for all of us, and anything less is just not acceptable. They will take their time. They will continue to listen. They will do this right. Because now it’s their turn.

“If you’re going through hell, keep going.”

For last night’s midterm, I needed to memorize the definition of the word “trajectory,” as it relates to one’s life, stated as “Relatively stable long-term processes and patterns of events, involving multiple transitions.” As I

The Coronavirus Slide

About five minutes before Gianna shot these pics of our spontaneous dancing to the Cha Cha Slide, (which I’m clearly not very skilled at, but do have the ability to laugh at myself whilst doing,)

Life Imitates Birth, As Per Usual

Nine months ago today, a new life was conceived. Nine months ago today, I began my day by walking my son into an operating room, for a pseudo-routine jaw surgery, as much as any surgery

Home is Where Your Nest Is

It's 1:49 in the morning. I am keeping watch over my son while he sleeps to ensure nothing happens to compromise his breathing and/or health. (These duties are shared by the nurse, who so kindly

Ooh Child…

Today, but a sheer stroke of luck, I had a break in my schedule. Instead of filling it with an appointment request, I took the time to go to a yoga class led by one

The Light at the End of the ICU Tunnel!

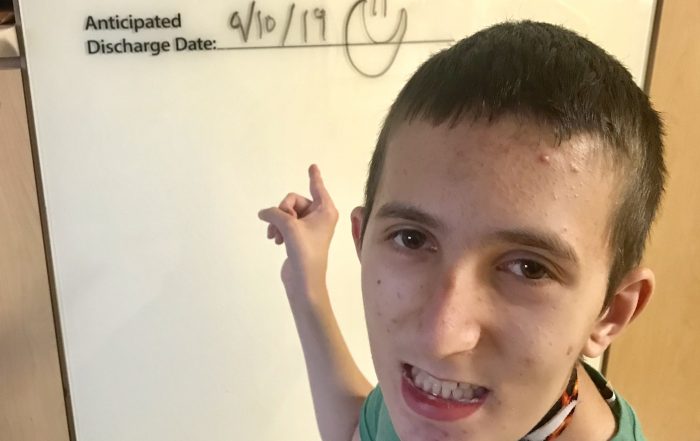

For over three months, I have looked at that white board in his room at the “Anticipated Discharge Date.” Blank. Empty. No ideas. (Save for Gianna who wrote a while back, “We don’t know.”) No end